I spend a good chunk of my time online, ogling art. I scroll through museum Instagram feeds, browse institutional databases. I also talk a lot with people who, in a variety of contexts, are competitors in the relentless ‘attention economy’: the battle for eyeballs.

The internet is an information miracle. I love having the world within my immediate reach. But I am troubled, increasingly, by the flattening of context and feeling that comes with this access. I feel we are sliding from creative means to attentive ends, from form to fungibility.

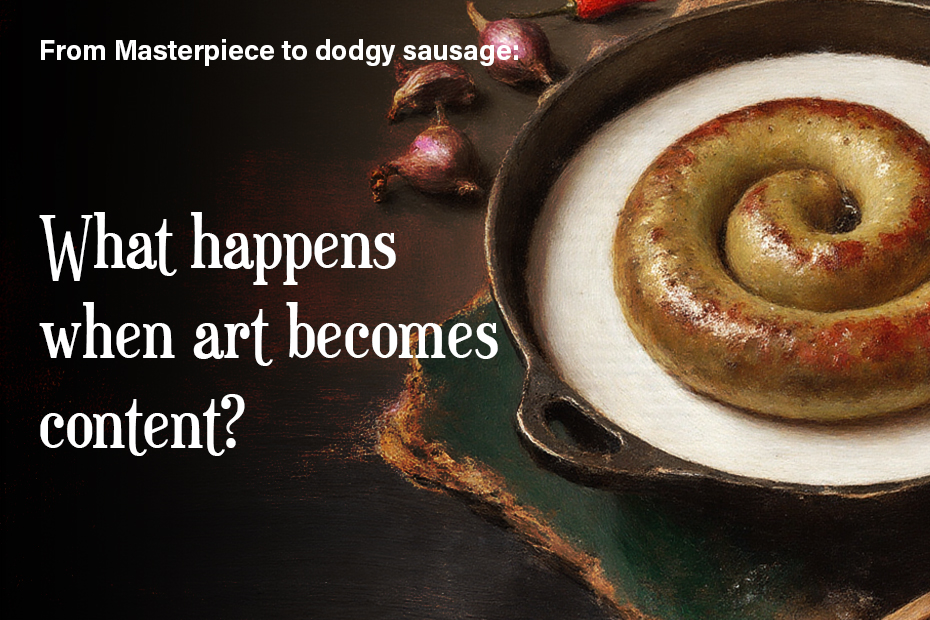

What I am talking about is both technological and attitudinal. The technology is magically smooth: it serves a Rembrandt masterpiece with the same blithe efficiency as a whimsical dance, measuring the impact as it lands. The attitude is that we accept measurement as master, so we see whatever gets our likes. As a result, our feed is filled with a steady stream of immediate hits, rendered in the same smooth space, like a neverending Cumberland sausage, stuffed with juicy content.

I have heard myself, and others, refer to art as ‘content’. This bothers me.

Content is not a harmless catchall. Within it lurks a cynical agnosticism. Content is anything that you want. The sausage could be wholesome, truthful, or beautiful, or it could be fake, false, and frightful. The way it is appraised remains the same: does it get consumed? That’s what matters.

Content, as a media term, performs several insidious tricks:

- it renders everything, no matter what;

- it implies a void that must be filled;

- it puts the end before the means.

So: please, let’s not call art ‘content’.

Consider Rembrandt’s Isaac and Rebecca, (c. 1665-1669 – also known as The Jewish Bride). On a standard screen, the painting is a lovely, warm image. But what’s lost is the thick, sculptural impasto on the man’s golden sleeve—paint so proud that it physically catches the light, giving the tender gesture its emotional and literal weight—is flattened into a smooth, surfaceless image. The facture—the visible, tangible evidence of the artist’s hand—is erased. That’s how the sausage is made: all the texture, all the uniqueness, is ground down.

I’m not alone in my unease. A new term is emerging that describes a reaction to this textureless proliferation: antimemetics. It describes an active retreat by artists and art-lovers into spaces and ideas that resist virality.

I find this attractive, but not straightforwardly. On one hand, the word ‘antimimetic’ describes a quality great art has always had. Think of the complex iconography in a Renaissance painting, like Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, where a single lit candle symbolises the presence of God and a dog represents fidelity. This dense layering of meaning is part of art’s aspirational aura; it demands knowledge and rewards patience. Not everyone is going to ‘get it’.

On the other hand, incomprehensibility can feel like a sneer. For artists, antimemetics is a valid tactic against the tyranny of the algorithm, a way to preserve creative autonomy. But could it also be a flex? A sign that you’re in the right club, getting the right invites, being ‘in the know’?

I think we need another path.

At Vieunite, we use digital technology to bring the art experience into homes and businesses. Unlike a phone or a TV, our Textura canvas is designed specifically to display the haptic, textural quality of art. Of course, it’s not the same as standing before the original Rembrandt. But because we have worked obsessively to maintain that feeling of physical presence, when you see an image on a Textura canvas, it feels like an exhibition, not a fleeting impression. Our screens were not designed with indifference to what they display. They are built with art in mind.

And there’s something else we do differently. Every work of art on our platform is fully attributed, with the artist’s biography and contextual descriptions available via our app. We strive to restore the context, the story, the intention behind the image. We want to give you the tools to understand not just the picture, but its deeper meaning—its iconography, its presence.

We don’t want to make art like everything else.

What we want is to get you closer to art.

Benedict is Vieunite’s Cultural Director and a lecturer at Nottingham Trent University.