The Royal Pavilion at Brighton is one of Britain’s most unique and eccentric buildings. It looks “like something conjured from a dream or perhaps an extravagant dare.” But what kind of man was the flamboyant and extravagant George IV, the “party prince” who built this palace? Why did he choose a style so wildly different from the rest of Europe, seemingly oblivious to the revolutions and wars raging just across the Channel?

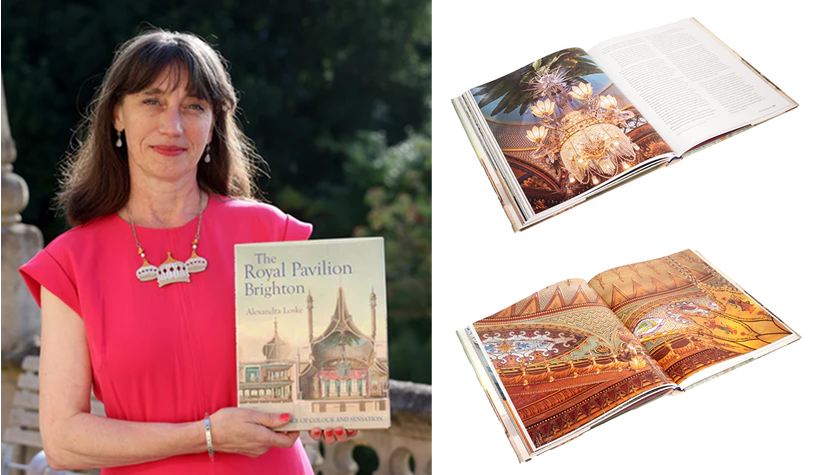

Join Dr. Benedict Carpenter van Barthold, Cultural Director at Vieunite, as he uncovers the history, scandal, and architectural genius behind this extraordinary royal residence in a new video. To help him peel back the layers of this fascinating building, he’s joined by Dr. Alexandra Loske, the Royal Pavilion’s leading expert and curator.

The Man and the Mirage

I’ve been aware of the Royal Pavilion since visiting Brighton in the early 90s, and even then, I thought it was a remarkable edifice. In the late evenings, it seemed to glow like a mirage, a barely believable exotic confection surrounded by the relatively drab texture of modern architecture. My interest deepened when Vieunite licensed several exclusive images of the Pavilion into our library. This led to a deeper interest in the building and – as I learned more – the fascinating personal stories behind it.

Dr Loske describes the Pavilion’s aesthetic as “romantic, picturesque, enchanting,” and something that “looks like no other building in this country.” It’s an almost dreamlike vision with its spires and domes appearing out of the urban cityscape of Brighton. This bewildering and beguiling effect is entirely deliberate. The building is intended to transport the visitor into another realm, a world of sensual indulgence.

But that’s not how the Pavilion began, because the Pavilion evolved in stages. George IV’s first retreat, built by architect Henry Holland in the 1780s, was an elegant Neoclassical building, constructed decades before George was King, when he was merely a dazzling party prince. He famously came to Brighton for a “sea cure,” which also served as a convenient figleaf to escape the strict London court life and his father, King George III, with whom he didn’t get along. As a young man, a contemporary described him as someone who would “drink, wench, and swear like a man who at all times would prefer a girl and a bottle to politics and a sermon…”

He began the building’s transformation in earnest from 1815 onwards, enlisting the creative genius of architect John Nash to “catch up” with the Moorish-style stables he had already built. This was a politically opportune time, as Napoleon had just been defeated at Waterloo. It’s an intriguing thought that George’s shift to Indian-inspired architecture may have been a way to avoid appearing “too Francophile,” while still indulging his theatrical and extravagant tastes.

Art, Science, and a Celebrity Chef

The Pavilion is an architectural marvel and a playground for the senses, but it’s also a testament to Regency-era innovation. Inside, the interiors are a dramatic departure from the Neoclassical exterior, reflecting George’s love of Chinese-inspired design. The building is filled with vibrant, “highly saturated” paints made from exotic pigments like “Chinese vermilion” and “cochineal,” a transparent red created from crushed parasitic insects from South America. George even embraced a new chemical pigment, chrome yellow, which was later famously used by Vincent van Gogh in his Sunflowers.

The Pavilion was a stage for George’s legendary feasts. Antoine Carême, a renowned French chef nicknamed “the Palladio of Patisserie,” worked for George in 1816. Carême was a master of elaborate sugar sculptures and aspired to be an architect himself. Remarkably, a quarter of the building’s ground plan was devoted to food. The Great Kitchen featured a “Smoke Jack,” a sophisticated spit roast that used a fan system in the chimney to keep things rotating. There was even a steam table to keep all the extravagant dishes warm – a necessity when a feast might feature 100 dishes.

Despite this public grandeur, the building also has its intimate narratives. The spectacular roofline, for example, forced the private apartments upstairs to be small and low ceilinged. George’s move to the ground floor later in life was partly due to his declining health, and he installed a lavish, custom-built bathroom with a “miniature pool” and steam contraptions. The idea of a “sea cure” that brought him to Brighton as a young man became a necessity in his later years. He was even attended by his “royal shampooer,” Sake Dean Mahomed, who offered Indian-style massage treatments.

A Legacy for the People

George’s reign ended in 1830, and the Pavilion was eventually sold by Queen Victoria to the people of Brighton for a bargain price, as it was assumed the building would be pulled down. Victoria moved the furnishings to Buckingham Palace to outfit her new wing. Over the years, many of the original objects have been returned on loan, and it is thanks to a detailed book of aquatints published by John Nash that restoration efforts can be so historically accurate.

The Pavilion is now run by the Royal Pavilion and Museums Trust, an independent charity. The Trust’s mission is to preserve this fragile and complex building. To support this vital work,as Alexandra says, “come and visit, spend time, spend money here, and spread the word.” And when you do, be sure to look up and be amazed by the spectacular Dragon Chandelier in the Banqueting Room.

Of course, another way of supporting the work of the Trust is to bring some Regency opulence into your own home, by enjoying some of the Pavilion’s images on your Textura screen.

To go deeper into the stories of this magnificent building, watch the full video with Dr. Alexandra Loske. You can also pick up her new book, The Royal Pavilion, Brighton: A Regency Palace of Colour and Sensation, published by Yale University Press. You can find it here.

Watch the full interview:

Benedict is Vieunite’s Cultural Director and a lecturer at Nottingham Trent University.